Older people's travel and mobility needs

At the Centre for Transport & Society at the University of the West of England, along with my researcher, Hebba Haddad, we carried out interviews and focus groups with drivers and ex-drivers, to look at transport and travel needs among older people and developed a hierarchical model of transport needs.

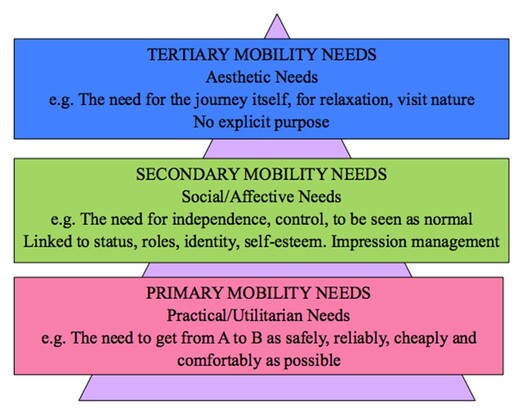

The model has three levels based on when in the conversation the need arose.

At the bottom level, the most commonly cited need was practical or utilitarian need, that travel got people from A to B to do the things they wanted to do, as cheaply, as quickly and reliably, as possible, with minimal effort needed.

A middle level emerged in the conversations a little later on, that mobility is more than just A to B, that it also related to psychosocial or social/affective aspects of life, such as independence, freedom, status, roles etc.

Finally, a less common need emerged much later on in the conversation and that was the need for travel for its own sake, to see beautiful surroundings, to feel movement, to test cognitive skills of driving or travelling, a sort of touristic aspect of travel need.

More recently, in a study with older people who use different modes of transport, I have discovered that driving a car helps fulfil utilitarian needs to a maximum and without a car, affective and aesthetic needs would not be met. Walking meets aesthetic needs, some psychosocial needs but few practical needs. Using the bus can meet practical and aesthetic mobility needs but not psychosocial mobility needs of older people. Getting a lift can meet practical mobility needs and sometimes can be aesthetic mobility needs but does not meet psychosocial mobility needs of older people.

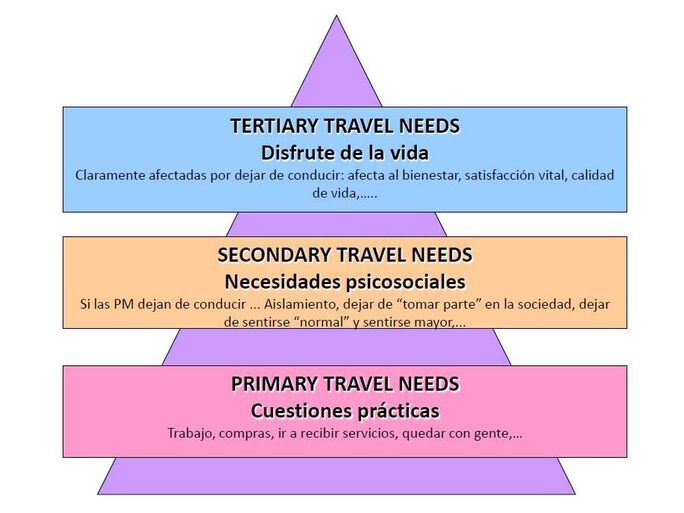

10 years on from development of that model, Hebba and I have taken time to revisit it. The model of travel needs has been cited well over 150 times and been used as a basis for understanding older people’s travel needs in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Israel, Malta and Sweden and translated into Spanish (Yanguas, 2014), Greek (Dikas, 2014) and Welsh (Musselwhite, 2016).

We used a reflective model of analysis. We looked to see if the needs existed in 5 other research projects we had been involved with, that had over 150 participants. We took feedback from academics, policy makers and practitioners working in the field from 25 conferences the model has been presented at. We took the feedback on the original peer review for the journal article (published in 2010) and looked at 19 articles where the model had been discussed in depth (from the 119 articles it has been cited in). We also took feedback from older people themselves on the model and whether it fitted their lives well.

Overall, we were generally happy the model should stay the same. Similar categories emerge with other data and these categories are pretty useful for policy and practice to understand the multifaceted nature of transport and travel in later life. The model can be applied potentially to other age groups, and some research would be useful to identify if this were the case. Policy and practitioners would like the model to be enumerated to help them when justifying the cost-benefit analysis of alternative travel modes to the car in later life. The model is similar to models in other domains and has been applied to taking journeys on the bus, the built environment and to ICT practices to support independent living.

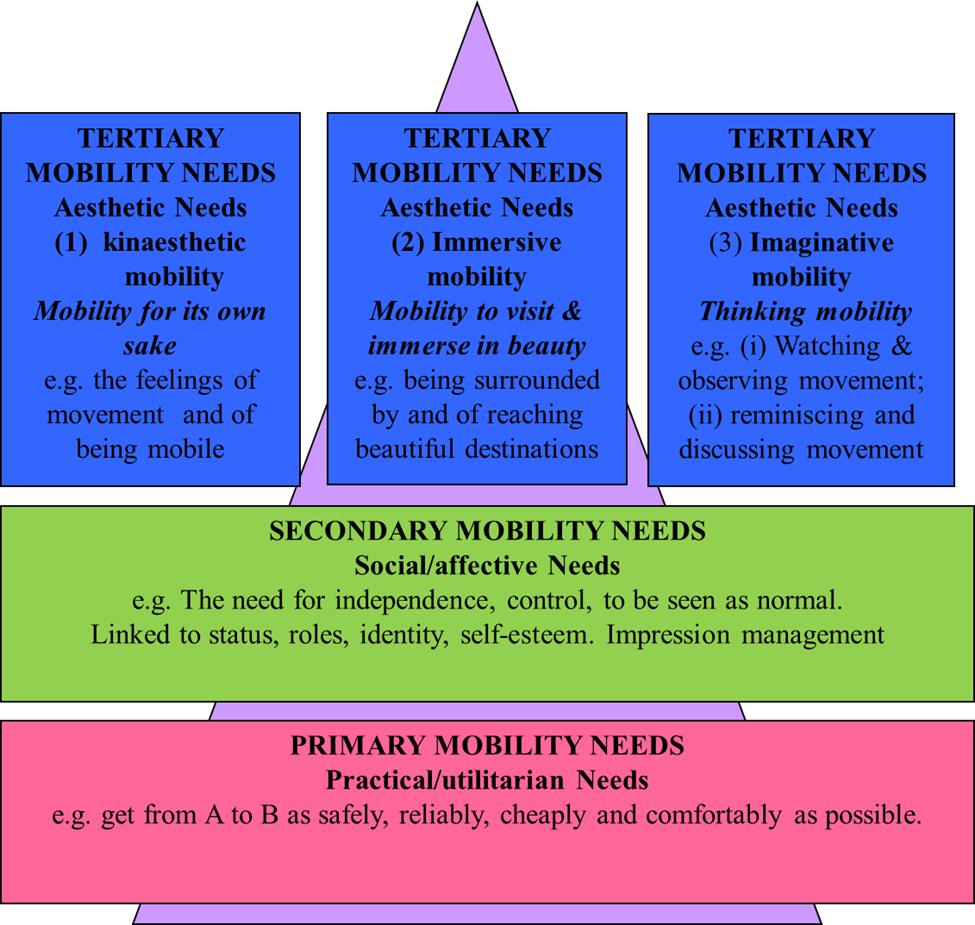

The only significant change is in the final aesthetic category, where further we split the model into three different types of aesthetic needs, which are interrelated but different from one another:

(1) Kinaesthetic mobility. The need to feel movement itself.

(2) Immersive mobility. A recent paper I wrote on discretionary travel shows that journeys to see the sea or the forest, going out for a drive or going the long way round on the way home from a more “purposeful” visit to the hospital or shops, were crucial to people’s wellbeing.

(3) Imaginative mobility. Watching and observing others mobility and reminiscing about travel and mobility from the past. This was especially the case for people who had physical mobility difficulties that meant they couldn’t get out and about as much as they once did. A way of connecting to high levels of mobility without having to physically be mobile.

Blog:

Revisiting the travel and transport needs of an ageing population

Journal papers:

Musselwhite, C.B.A. and Haddad, H. (2018). Older people’s travel and mobility needs. A reflection of a hierarchical model 10 years on. Quality in Ageing and Older Adults, 19(2), 87-105.

Musselwhite, C.B.A. (2017) Exploring the importance of discretionary mobility in later life. Working with Older People, 21, 1. 49-58.

Musselwhite, C. and Haddad, H. (2010). Mobility, accessibility and quality of later life. Quality in Ageing and Older Adults. 11(1), 25-37

Book chapters

Musselwhite, C.B.A. (2018). Mobility in Later Life and Wellbeing in M.Friman, D.Ettema and L.Olsson (eds.) Quality of Life and Daily Travel. Applying Quality of Life Research (Best Practices). Cham, Switzerland: Springer. Pp 235-251.

Reports

Musselwhite, C. and Haddad, H. (2008). Prolonging safe driving through technology. Final Report. UWE research report

Presentations

Musselwhite, C.B.A. and Haddad, H. (2018) Older people’s travel and mobility needs. A reflection of a hierarchical model 10 years on. Proceedings of the 50th Annual Conference of the Universities' Transport Study Group (UTSG), University College London 4 January

Musselwhite, C.B.A. (2015). Innovation in transport and mobility provision: Fun-ctional transport solutions Invited presentation to Community Transport Association's Annual Westminster Conference, Institute of Civil Engineers, One Great George Street, Westminster, UK. 25th November

Musselwhite, C.B.A. (2015). Providing for fun for functional mobility in later life. Invited presentation at ILC-UK Report Launch: The Future of Transport in an Ageing Society. House of Lords, Westminster, London, UK. 18 June.

Musselwhite, C.B.A. (2015). Understanding mobility and wellbeing in older age, Keynote address Design for Wellbeing: Innovative research methods for understanding older people’s everyday mobility conference, Oxford Brookes University, UK. 21 April.

Musselwhite, C. and Haddad, H. (2008) Travel and well-being. Travel independence and car dependence: An exploration of older drivers travel and driving needs. British Society of Gerontology Conference, Bristol, UK, September 2008.

Musselwhite, C. B. A. and Haddad, H. (2008). A Grounded Theory exploration into the driving and travel needs of older people. Proc. 40th Universities Transport Study Group Conference, University of Southampton, Portsmouth, January

Musselwhite, C. and Haddad, H. (2007) Putting your foot down. Invited to present at the Older People on the Move workshop, University of Reading.

The model has three levels based on when in the conversation the need arose.

At the bottom level, the most commonly cited need was practical or utilitarian need, that travel got people from A to B to do the things they wanted to do, as cheaply, as quickly and reliably, as possible, with minimal effort needed.

A middle level emerged in the conversations a little later on, that mobility is more than just A to B, that it also related to psychosocial or social/affective aspects of life, such as independence, freedom, status, roles etc.

Finally, a less common need emerged much later on in the conversation and that was the need for travel for its own sake, to see beautiful surroundings, to feel movement, to test cognitive skills of driving or travelling, a sort of touristic aspect of travel need.

More recently, in a study with older people who use different modes of transport, I have discovered that driving a car helps fulfil utilitarian needs to a maximum and without a car, affective and aesthetic needs would not be met. Walking meets aesthetic needs, some psychosocial needs but few practical needs. Using the bus can meet practical and aesthetic mobility needs but not psychosocial mobility needs of older people. Getting a lift can meet practical mobility needs and sometimes can be aesthetic mobility needs but does not meet psychosocial mobility needs of older people.

10 years on from development of that model, Hebba and I have taken time to revisit it. The model of travel needs has been cited well over 150 times and been used as a basis for understanding older people’s travel needs in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Israel, Malta and Sweden and translated into Spanish (Yanguas, 2014), Greek (Dikas, 2014) and Welsh (Musselwhite, 2016).

We used a reflective model of analysis. We looked to see if the needs existed in 5 other research projects we had been involved with, that had over 150 participants. We took feedback from academics, policy makers and practitioners working in the field from 25 conferences the model has been presented at. We took the feedback on the original peer review for the journal article (published in 2010) and looked at 19 articles where the model had been discussed in depth (from the 119 articles it has been cited in). We also took feedback from older people themselves on the model and whether it fitted their lives well.

Overall, we were generally happy the model should stay the same. Similar categories emerge with other data and these categories are pretty useful for policy and practice to understand the multifaceted nature of transport and travel in later life. The model can be applied potentially to other age groups, and some research would be useful to identify if this were the case. Policy and practitioners would like the model to be enumerated to help them when justifying the cost-benefit analysis of alternative travel modes to the car in later life. The model is similar to models in other domains and has been applied to taking journeys on the bus, the built environment and to ICT practices to support independent living.

The only significant change is in the final aesthetic category, where further we split the model into three different types of aesthetic needs, which are interrelated but different from one another:

(1) Kinaesthetic mobility. The need to feel movement itself.

(2) Immersive mobility. A recent paper I wrote on discretionary travel shows that journeys to see the sea or the forest, going out for a drive or going the long way round on the way home from a more “purposeful” visit to the hospital or shops, were crucial to people’s wellbeing.

(3) Imaginative mobility. Watching and observing others mobility and reminiscing about travel and mobility from the past. This was especially the case for people who had physical mobility difficulties that meant they couldn’t get out and about as much as they once did. A way of connecting to high levels of mobility without having to physically be mobile.

Blog:

Revisiting the travel and transport needs of an ageing population

Journal papers:

Musselwhite, C.B.A. and Haddad, H. (2018). Older people’s travel and mobility needs. A reflection of a hierarchical model 10 years on. Quality in Ageing and Older Adults, 19(2), 87-105.

Musselwhite, C.B.A. (2017) Exploring the importance of discretionary mobility in later life. Working with Older People, 21, 1. 49-58.

Musselwhite, C. and Haddad, H. (2010). Mobility, accessibility and quality of later life. Quality in Ageing and Older Adults. 11(1), 25-37

Book chapters

Musselwhite, C.B.A. (2018). Mobility in Later Life and Wellbeing in M.Friman, D.Ettema and L.Olsson (eds.) Quality of Life and Daily Travel. Applying Quality of Life Research (Best Practices). Cham, Switzerland: Springer. Pp 235-251.

Reports

Musselwhite, C. and Haddad, H. (2008). Prolonging safe driving through technology. Final Report. UWE research report

Presentations

Musselwhite, C.B.A. and Haddad, H. (2018) Older people’s travel and mobility needs. A reflection of a hierarchical model 10 years on. Proceedings of the 50th Annual Conference of the Universities' Transport Study Group (UTSG), University College London 4 January

Musselwhite, C.B.A. (2015). Innovation in transport and mobility provision: Fun-ctional transport solutions Invited presentation to Community Transport Association's Annual Westminster Conference, Institute of Civil Engineers, One Great George Street, Westminster, UK. 25th November

Musselwhite, C.B.A. (2015). Providing for fun for functional mobility in later life. Invited presentation at ILC-UK Report Launch: The Future of Transport in an Ageing Society. House of Lords, Westminster, London, UK. 18 June.

Musselwhite, C.B.A. (2015). Understanding mobility and wellbeing in older age, Keynote address Design for Wellbeing: Innovative research methods for understanding older people’s everyday mobility conference, Oxford Brookes University, UK. 21 April.

Musselwhite, C. and Haddad, H. (2008) Travel and well-being. Travel independence and car dependence: An exploration of older drivers travel and driving needs. British Society of Gerontology Conference, Bristol, UK, September 2008.

Musselwhite, C. B. A. and Haddad, H. (2008). A Grounded Theory exploration into the driving and travel needs of older people. Proc. 40th Universities Transport Study Group Conference, University of Southampton, Portsmouth, January

Musselwhite, C. and Haddad, H. (2007) Putting your foot down. Invited to present at the Older People on the Move workshop, University of Reading.